Introduction

Over the past five years, two key social justice questions have emerged in the European Union. On one hand, as a result of the Eurozone crisis and related austerity measures, poverty and inequality have dramatically increased in southern Europe. On the other hand, the intensification of the “refugee crisis” that started in early 2011 has led to increasing numbers of deaths of people attempting to cross the Mediterranean, and has brought back to the forefront latent xenophobia throughout the European Union.

In different ways, both of these questions—the economic crisis and austerity on one hand, and the “refugee crisis” on the other—raise the broader problem of who fully “belongs” in Europe. In other words, whose social and economic rights are to be respected? Who can access the basic premises for the building of a dignified life?

This paper analyzes how the combination of austerity measures on one hand and the refugee crisis on the other are drawing differential lines of exclusion in Europe. After documenting these lines of exclusion and their effects on people’s daily lives, the paper analyzes different political movements and parties that are emerging in response to the economic crisis.

The paper argues that in order to create a more fair and inclusive notion of Europe, it is necessary not only to defend and reinstate social-protection systems that are currently being dismantled by austerity, but also challenge longer term notions of who fully “belongs” in Europe. In other words, it is necessary to couple advocacy for social and economic rights with a commitment to challenge longer term dynamics of exclusion along lines of citizenship, ethnicity, and religion.

Stylianos Papardelas | Anamoni

Austerity

What Is Austerity?

Over the past half decade, various European countries have been experiencing one of the most dramatic economic crises of the past century. As the effects of the 2007–2009 US subprime mortgage crisis and the 2007–2008 financial crisis rippled across the Atlantic, various fiscally stressed states were forced to borrow heavily in order to keep their banks afloat, leading to an increased accumulation of public debts. Between 2010 and 2011, three states (Greece, Portugal, and Ireland) became insolvent, requiring a bailout package from the European Union and the International Monetary Fund, while Spain and Italy were also at risk.1)http://www.bbc.com/news/business-13856580; Varoufakis and Holland, “A Modest Proposal.”

. . . in order to create a more fair and inclusive notion of Europe, it is necessary not only to defend and reinstate social-protection systems that are currently being dismantled by austerity, but also challenge longer term notions of who fully “belongs” in Europe.

As a condition for bailout funds, these countries were forced to cut public spending and increase government revenue by passing a series of austerity measures. While these were primarily implemented in the southern European countries most affected by the sovereign debt crisis, similar measures were also taken in other parts of the European Union, most notably in the United Kingdom under David Cameron’s government.

Austerity is an umbrella term that includes a range of different policies sharing the stated aim of reducing public spending, increasing government revenues, and reducing the cost of labor in order to make countries more attractive to private investment. Although policies have varied from country to country, they have generally included measures such as reform to the pension system (e.g., raising the pensionable age, cutting pensions), cuts to health care and social services, increases in regressive taxes (such as VAT), and the liberalization of the labor market (though, among other things, the erosion of collective bargaining power).2)Caritas Europa, The European Crisis

While the weight of these policies varied from country to country, depending on their precrisis economic condition and their existing social-protection mechanisms, they have generally led to an increase in poverty and inequality, including both increased numbers of people living in poverty and intensification of poverty.3)Caritas Europa, The European Crisis; IFRC, Think Differently; Oxfam, A Cautionary Tale While the economic crisis and austerity measures have affected various EU countries, this paper focuses specifically on Spain, Greece, and Italy—countries that have been at the forefront of the “refugee crisis”4)Greece and Italy have been more strongly hit than Spain by the current arrival of refugees. and that have also seen the emergence of the largest antiausterity movements and parties.

Social and Economic Effects of the Economic Crisis and of Austerity Measures

The main consequences of the crisis and related austerity policies have been an increase in poverty and inequality. Even if austerity policies were to help relaunch the private sector, as their proponents suggest, they would create a highly inequitable growth.5)Oxfam, A Cautionary Tale. The increase in poverty is mainly due to unemployment, to changes in working conditions (e.g., decrease of the minimum wage, increase of flexible and precarious forms of employment), and to pension cuts.

Regarding the first point, in 2013 the unemployment rate across the European Union was 11 percent, or twenty-six million people.6)Caritas Europa, The European Crisis A high proportion of this unemployment is long term, which—depending on the national welfare system—may lead to the loss of unemployment benefits. Among the unemployed, youth have been the most affected throughout southern Europe (Italy, Spain, Greece).

In addition to unemployment, all these countries have also seen a rise in the number of working poor. The reasons for the increase of this category are multiple, ranging from the increased use of temporary contracts,7)Caritas Europa, The European Crisis to working for multiple months without receiving a salary,8)IFRC, Think Differently as well as cuts to minimum wage enforced as part of austerity measures,9)Caritas Europa, The European Crisis and to a general fall in the real value of wages.

Finally, cuts to pensions—such as the deindexation of pensions from cost-of-living variations that was imposed as part of austerity packages in Italy10)Caritas Europa, The European Crisis—have had multiplier effects on poverty, as often pensioners’ incomes provide support for other family members. In some cases, one person’s pension is the only source of income of an extended family.11)Caritas Europa, The European Crisis, IFRC, Think Differently Some examples of the manifestation of poverty in daily life are the inability of households to afford winter heating in Greece,12)Forty-three percent of the families assisted by the Red Cross in Spain were unable to afford heating in winter months [IFRC, Think Differently]. extended families moving in together in Spain to save on costs, and increased homelessness of divorced men in Italy, who are unable to both support their former spouse and children and provide housing for themselves.13)IFRC, Think Differently

Overall, the Spanish Red Cross has seen the numbers of people who make use of its emergency assistance program rise from 900,000 to 2.4 million in only four years.14)IFRC, Think Differently

The increase in poverty has gone hand in hand with an increase in inequality. In both Greece and Spain, countries that have suffered the effects of the crisis and of austerity measures most severely in terms of unemployment, the last half decade has been characterized by extreme social polarization. In Greece, the top 20 percent of the population can rely on a disposable income (posttax) of 41,000 euros per year, while the bottom 20 percent earns less than 7,317 euros per year.15)Caritas Europa, The European Crisis This situation is similar to Spain, where the income of the top 20 percent of earners is over seven times more than the lowest 20 percent.

The increase in poverty and in inequality is exacerbated by cutbacks to social services, implemented as part of austerity policies. Alongside pensions and unemployment benefits, health spending has been cut throughout countries implementing austerity policies, ranging from increases in copays in Italy to the tying of health care to employment in some parts of Spain.16)McKee, Karanikolos, Belcher, and Stuckler, “Austerity: A Failed Experiment.” In essence, the banking and debt crisis are transforming into a social and public-health crisis without precedent in the last fifty years in western Europe.

Table 1. Unemployment, poverty, and austerity measures in southern Europe

| Spain | Greece | Italy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployment | 24.5% | 26.5% | 12.7% |

| Youth unemployment | 53.2% | 52.4% | 42.7% |

| People at risk of poverty or social exclusion | 29.2% | 36.0% | 28.1% |

| In-work population at risk of poverty17)Percentage of population over eighteen. | 12.5% | 13.4% | 10.8% |

| Main austerity measures |

|

|

|

Source: Eurostat; Caritas Europa, The European Crisis.

If, as this section has shown, the effects of the crisis and austerity measures have been experienced by the population of southern Europe at large, non-EU citizens have been particularly hard hit. Before exploring this in more detail, however, it is necessary to understand the broader context of migration to southern Europe, which has most recently come to international attention through the “refugee crisis.”

Stylianos Papardelas | Anamoni

The “Refugee Crisis”

Numbers and Context

The arrival of migrants to Europe by boat is not a new phenomenon. As the Schengen Agreement implemented in the mid-1990s allowed for freedom of movement within the European Union, many European countries tightened their border controls and implemented more restrictive visa policies. As the pathways to travel to Europe became more limited, undocumented migration rose as other alternatives to enter the European Union were no longer available. In this context, the arrival of migrants by sea became more common.

In essence, the banking and debt crisis are transforming into a social and public-health crisis without precedent in the last fifty years in western Europe.

These crossings further intensified in the aftermath of the uprisings in the southern and eastern Mediterranean in early 2011, due to both the increase in armed violence in some countries (such as Syria and Libya) and to the decreased surveillance of North African coasts. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, in fact, both Tunisia and Libya had signed migration-control accords with the European Union. However, the political void that characterized the first months of 2011 in Tunisia allowed for over 20,000 migrants to leave the country’s shores. Similarly, ongoing instability in Libya led to a decreased control of the country’s coasts, allowing migrant-smuggling operations to flourish there.

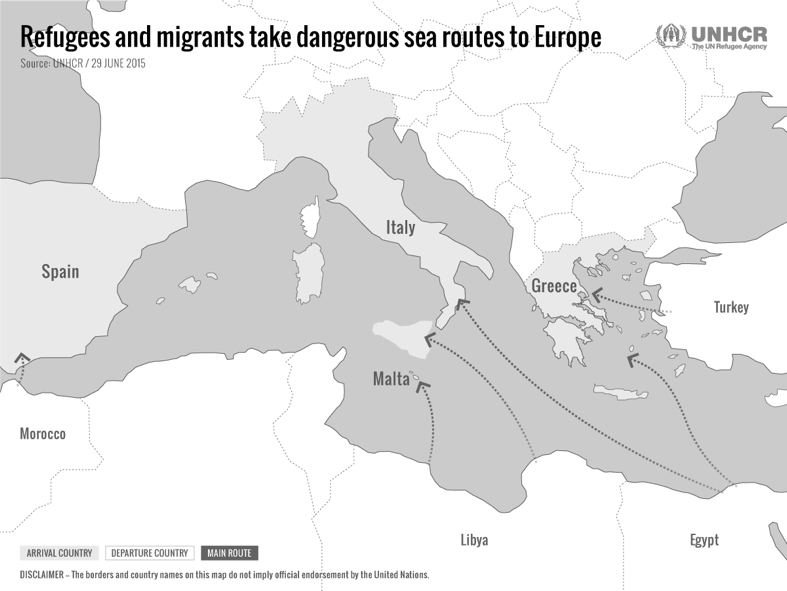

Figure 1. Main migrant routes to Europe, 2015 18)http://tracks.unhcr.org/2015/07/the-sea-route-to-europe/

Figure 1. Main migrant routes to Europe, 2015 | Source: UNHCR, http://tracks.unhcr.org

The numbers of migrants and refugees who have attempted to cross the Mediterranean over the past year have been substantial. According to the International Organization for Migration, in 2015 over a million migrants and refugees arrived at European shores.19) https://www.iom.int/news/irregular-migrant-refugee-arrivals-europe-top-one-million-2015-iom In the first two months of 2016, almost 130,000 migrants and refugees had already crossed the Mediterranean, reaching the total number of 2014 arrivals in only nine weeks.20) https://www.iom.int/news/mediterranean-migrant-arrivals-2016-near-130000-deaths-reach-418 Asylum seekers originate mainly from Syria and Sub-Saharan Africa (Eritrea, Somalia, Nigeria, Mali, Gambia, Senegal).21)http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/04/20/world/europe/surge-in-refugees-crossing-the-mediterranean-sea-maps.html?_r=0

In the first two months of 2016, almost 130,000 migrants and refugees had already crossed the Mediterranean, reaching the total number of 2014 arrivals in only nine weeks.

The dangers of Mediterranean crossings are extreme, making the Mediterranean the global border region with the highest mortality rate.22)http://missingmigrants.iom.int/ In 2014, more than 3,200 migrants died while attempting to cross the Mediterranean. In 2015, the numbers had risen to 3,800. By the end of March 2016, over 700 migrants had already died.23)http://missingmigrants.iom.int/mediterranean

Figure 2. Migrant deaths in the Mediterranean24)http://missingmigrants.iom.int/mediterranean

FIGURE 2. Migrant Deaths in the Mediterranean

Political Climate

The arrival of migrants and asylum seekers has attracted considerable political attention, both in the countries where they land and within the European Union more broadly. Due to present migration routes, the bulk of refugees have been landing in Greece and in southern Italy,25)http://frontex.europa.eu/trends-and-routes/migratory-routes-map/ two of the areas that have suffered most profoundly from the economic crisis and from austerity measures.

While there have been examples of solidarity from local inhabitants toward the migrants, there have also been occasions of hostility. This is particularly the case in contexts where a populist right-wing discourse frames migrants and refugees as a liability to countries that are already struggling with the effects of austerity.26)Akalin, “Dispossessed Immigrants”; Carastathis, “Blood, Strawberries.”

In addition to these local dynamics, additional tensions have also emerged between different European countries on the management of refugees who arrived on the continent’s southern coasts. Germany’s agreement to resettle large numbers of Syrian refugees within its borders is a relatively new development. Previously, different northwestern European countries have been reluctant to play a role in the crisis, whether by providing logistical and financial aid to Italy and Greece or by resettling some migrants and refugees. Regarding the former, the Italian naval operation Mare Nostrum was suspended in December 2014 due to the lack of funding support from other European countries, leading to a spike in numbers of deaths at sea in early 2015.27)http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/oct/31/italy-sea-mission-thousands-risk Regarding the latter, due to European refugee regulations (and specifically the Dublin system),28)http://www.ecre.org/topics/areas-of-work/protection-in-europe/10-dublin-regulation.html refugees are required to apply for asylum in the EU country of first entry, thus putting considerable strain on countries at the southern border of Europe, such as Italy and Greece.

While local and national governments in Italy have repeatedly stressed that the arrival of migrants and refugees is a European problem,29)“La paura dell’invasione: ‘La Sicilia non può assorbire una maxi-ondata di sbarchi.’” La Repubblica, February 24, 2011 various northwestern European countries have been reluctant to participate in migrant resettlement schemes, as they claim that southern European countries take a much lower number of refugees. In some cases, northwestern European countries have also temporarily closed their borders to prevent the passage of non-EU migrants who had arrived to southern Europe. This happened repeatedly at the Ventimiglia land border between France and Italy.30)http://effimera.org/se-questa-e-europa-confini-austerity-e-guerra-di-gabriele-proglio/ As discussions over refugee and asylum seeker resettlement have progressed, many Eastern European countries have also expressed their reluctance to participate in these schemes.31)http://www.reuters.com/article/us-europe-migrants-orban-idUSKBN0TL0RF20151202

Reactions to the current “refugee crisis” at the local, national, and EU level cannot be fully understood without situating it within the broader framework of discussions about immigration in many European countries. In this regard, throughout the continent, the last decade has seen a general increase in hostility both toward new migrants and toward longtime residents and citizens of non-European descent. This hostility emerges in explicitly xenophobic movements (e.g., the marches against the “Islamification” of Germany)32)http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/dec/22/anti-islam-march-germany-sing-christmas-carols and also in claims of various mainstream European politicians about the “failure of multiculturalism.”33)International Organization for Migration, Fatal Journeys

At a day-to-day level, it emerges in tensions around access to jobs and welfare. This is clearly visible in the words of an unemployed Italian man, who complained to researchers about what he perceived as the preferential treatment of non-EU migrants in accessing resources: “If you go to the municipality, they tell you they are in the red…Maybe if an immigrant goes they will help him…I don’t think it is right because they should help Italians first, and then if there is something left over…I am not racist, god forbid…but…when you have a family, if I have an apple and there are five of us, I divide it in five parts. Then, if there is something left over and someone else, I give it to him, but I give the pieces to the family first…”34)De Luca, “La fatica della resilienza,” p. 235

“I am not racist, god forbid…but…when you have a family, if I have an apple and there are five of us, I divide it in five parts. Then, if there is something left over and someone else, I give it to him, but I give the pieces to the family first…”

By drawing the distinction between “us” and “them” along lines of nationality, these words point to a broader political climate in which the question of who fully “belongs” in Europe as a full subject entitled to rights and protections is still a highly contentious one.

The following section explores the intersection of austerity measures and migration in more detail, addressing firstly the specific way in which crisis and austerity measures are affecting non-EU migrants, and secondly the ways in which different antiausterity movements are addressing migration.

Stylianos Papardelas | Anamoni

Crisis, Austerity, and Migration

Effects of the Economic Crisis and Austerity on Non-EU Migrants

If the effects of the crisis and austerity are felt throughout the social body of southern European countries, non-EU migrants are affected in particularly strong ways. The main ones are increased unemployment, consequent loss of residency papers, and cuts to integration policies. Regarding the first point, according to Caritas, in the aftermath of the crisis throughout Europe, non-EU migrants are about twice as likely to be unemployed than EU nationals, and this unemployment is often extended over multiple months and even years.35)Caritas Europa, The European Crisis

Within this general pattern, there is considerable variation within countries. In Italy, the disparity in employment between migrants and Italian citizens has remained approximately the same, as the unemployment rates for both categories have risen simultaneously.36)Bonifazi and Martini, “Il lavoro degli.” In Spain, on the other hand, migrant workers were disproportionately hit by the crisis as many of them were employed in the construction sector, which was substantially brought to a halt after the burst of the construction bubble.37)Valls, Coll, and Rivera, “Migración neohispánica?”

The rise in unemployment has particularly serious effects on migrants whose residency status is contingent on employment, as is the case in Italy. Both Caritas and the Red Cross have noted that the proportion of migrants who have become undocumented has greatly increased among their assisted population.38)IFRC, Think Differently; Caritas Europa, The European Crisis Cuts in welfare implemented as part of austerity packages (such as cuts or limitation to unemployment benefits) have particularly affected non-EU migrants, who often are not able to rely on extended-family support networks.

The lived experience of the crisis, the risk of the loss of residence papers, and the absence of a safety net is captured by the words of a middle-aged Albanian migrant to Italy: “It is difficult for everyone…but maybe for Italians a little less because almost all of them have some savings…But for people like me who have no savings, it is a real problem. And then we also have the problem of the residency permit…after all I did to get papers…I risk losing my residency permit again. It is really difficult.”39)De Luca, La fatica della resilienza,” p. 232

While unemployment and loss of residency papers can mainly be attributed to the economic crises, austerity measures have had a more substantial impact on migrant integration programs, which have been hit across the European Union. However, according to a report by the Migration Policy Institute,40)Collett, Immigration Integration the most substantial cuts to migrant integration programs (be it through cuts to the programs themselves or through the transfer of the cost to migrants—for instance, by making migrants pay for language classes) have not occurred in the countries that were most hit by the crisis and consequent austerity measures. Instead, they occurred in the Netherlands and in the United Kingdom.

Thus, according to the report, the political climate has been as important as budget constraints in promoting cuts to migrant integration programs.41)Collett, Immigration Integration This leads directly to the following section that analyses how different political movements throughout Europe have addressed migration in the context of economic crisis and austerity measures.

. . . the political climate has been as important as budget constraints in promoting cuts to migrant integration programs.

The Political Climate Around Austerity and Migration

Movements and parties critical of austerity have articulated two main positions toward non-EU migrants. On one hand, some have made use of a nationalist rhetoric that does not consider migrants as part of the population hit by austerity, but as an additional burden that is subtracting resources from the national population. Examples of parties that promote this vision include the right-wing Anel Party in Greece or some fringes of the M5S in Italy.

These positions draw on a broader rhetoric of the European right (including parties that are not explicitly antiausterity) that considers migrant workers an external burden on welfare, which, at a time when the welfare state is shrinking, represents a threat to the social and economic rights of citizens. Examples of the rise of political movements who have adopted this rhetoric include Ukip in the United Kingdom42)Ukip, Believe in Britain (which also targets EU citizens who have migrated to Europe) and the National Front in France.

These positions draw on a broader rhetoric of the European right (including parties that are not explicitly antiausterity) that considers migrant workers an external burden on welfare, which, at a time when the welfare state is shrinking, represents a threat to the social and economic rights of citizens.

On the other hand, other antiausterity parties have combined their critiques of current political and economic policies with an inclusive political message that considers non-EU migrants as part of the social body affected by the crisis and austerity measures. The Spanish Podemos and Greek Syriza have advocated for migrant rights in the context of their broader antiausterity politics.

Regarding Podemos, part of the broad coalition of movements that came together in the M-15 demonstrations were explicitly concerned with migrant rights, and this concern has translated into the political orientation of the party.43)Podemos, El programa del cambio In Podemos’s 2015 program, in fact, the rights of immigrants in Spain are connected to the defense of the rights of Spanish emigrants abroad, and both are interpreted as part of promoting a universalist notion of citizenship. At the same time, the party also committed to halt deportations and work to close migration detention centers.44)Podemos, El programa del cambio

Syriza espoused similar politics, advocating for an acceleration of the asylum-petition process, promoting family reunification, repealing EU restrictions on migrant travel and advocating for the human rights of migrants in detention centers.45)Chen, “What Does Syriza’s Victory Mean”

The Italian Movimento Cinque Stelle has had a more contradictory position. The official spokesperson of the party, Beppe Grillo, adopted anti-immigrant positions while the elected deputies of the movement voted to rescind a law that criminalized undocumented migration. In local government, many of the movement’s representatives have adopted a very inclusive attitude toward migration, including Italian citizens of non-European descent in their lists, and publically advocate for reforms to citizenship law.

The electoral success of these three parties testifies to the widespread frustration with the existing social and economic order throughout southern Europe. Furthermore, their positions on migration (be they articulated by the leadership or the grassroots activists of the parties) suggest that there are openings to promote a social and economic rights agenda that is inclusive to the needs of migrants and asylum seekers, as well as to residents and citizens of non-European background.

However, the recent capitulation of the Greek antiausterity government to the demands of the Troika46)http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2015/07/syriza-survive-austerity-150716073159609.html raises the question of how much political leverage these movements can have in the current political conjuncture.

Stylianos Papardelas | Anamoni

Stakes and Prospects for the Future—Key Objectives

This paper has shown that various lines of exclusion and marginality are currently being drawn in the European Union: along lines of class (with the increase of poverty and inequality throughout southern Europe), of citizenship and ethnic background (with the “refugee crisis” in the background of anti-immigrant and xenophobic movements), and of regionalism (with increasing regional economic disparities between the northwestern “core” of Europe and its southern peripheries). In this context, political decisions have a central role in determining what European society will look like over the next few decades, how inclusive it will be, and whose economic, social, and political rights will be taken into account. Two issues will be particularly important.

The first concerns the future of the austerity measures that have been implemented in response to the crisis. As this paper has shown, their social costs have been tremendous: poverty and inequality have increased throughout southern Europe, access to health care has been compromised, and the most marginalized sectors of the population have borne the brunt of these measures.47)Caritas Europa, The European Crisis; Oxfam, A Cautionary Tale Anti-austerity movements and parties have emerged throughout southern Europe and enjoyed considerable electoral success but, for now, the political mainstream on both the left and right remains in favor of austerity policies as a necessary evil to revitalize the economy.

The second concerns the future of the political response to austerity, which so far has developed in two main directions. On one hand, movements such as Anel in Greece and some fringes of the Italian M5S consider non-EU migrants and asylum seekers to be extra burdens on the welfare of EU citizens, rather than fellow victims of the crisis.48)In the context of the United Kingdom and the destination of many EU migrants, right-wing parties define the circle of belonging even more narrowly by also portraying migrants from southern and eastern Europe as a source of labor competition and a drain on welfare. On the other hand, anti-austerity movements in Greece and Spain have combined a critique of austerity policies with an explicitly pro-migrant agenda, thus advocating for a broad and inclusive notion of “belonging” in Europe.

These dichotomies are not unique to Europe but are a recurring tension in many historic and contemporary settings, not least the United States. Will widespread economic hardship lead to a hardening of lines of exclusion, a narrow definition of belonging along lines of nationality, race or ethnicity, and a scapegoating of certain excluded groups? Or can such moments become an occasion to highlight and question the structural reasons for widespread poverty and inequality, and to create a broad and inclusive understanding of belonging while pushing for transformative change?

Will widespread economic hardship . . . become an occasion to highlight and question the structural reasons for widespread poverty and inequality, and to create a broad and inclusive understanding of belonging while pushing for transformative change?

In order to achieve the latter in the European context, it will be important to pursue two strategies simultaneously. On one hand, it will be important to reconsider the promise of austerity policies as a spur for economic rejuvenation, the type of growth that would occur were these policies successful, as well as their social costs. Continuing to develop critiques of austerity, giving them increased visibility and legitimacy, and building movements around them is a key way to create the political momentum to produce change.

At the same time, when talking about austerity it is important to adopt a broad and inclusive definition of the “we” who suffer as a consequence of austerity measures and to avoid defining the “we” strictly along lines of citizenship. Creating, promoting, and organizing around a broad, inclusive understanding of “who belongs” is a key precondition to creating a society that is truly inclusive and emancipatory for all.

Contact the author, Ilaria Giglioli, at giglioli@berkeley.edu.

Bibliography

Akalin, N. “Dispossessed Immigrants: The Reproduction of Racialization in the Times of Austerity Measures.” Historical Materialism Conference (unpublished paper) (2014).

Bartlett, J., C. Froio, M. Littler and D. McDonnel. New Political Actors in Europe: Beppe Grillo and the M5S. Demos, 2013.

Bonifazi, C. and M. Livi Bacci. Le migrazioni internazionali al tempo della crisi. Neodemos, 2014.

Bonifazi, C. and C. Martini “Il lavoro degli stranieri in tempo di crisi.” Le migrazioni internazionali al tempo della crisi. Neodemos, 2014.

Caritas Europa. The European Crisis and Its Human Cost, 2014.

Carastathis, A. “Blood, Strawberries: Accumulation by Dispossession and Austere Violence Against Migrant Workers in Greece.” World Economics Association Conferences 2014. Greece and Austerity Policies. Where Next for Its Economy and Society? (2014).

Chen, M. “What Does Syriza’s Victory Mean for Greece’s Immigrants.” The Nation (2015). http://www.thenation.com/article/what-does-syrizas-victory-mean-greeces-immigrants/.

Collett, E. Immigrant Integration in Europe in a Time of Austerity. Migration Policy Institute, 2011.

De Luca, V. “La fatica della resilienza. I lavoratori immigrati di fronte all’esperienza della disoccupazione. In D. Coletto, S. Guglielmi, & M. Ambrosini,” Perdere e ritrovare il lavoro: l’eperienza della disoccupazione al tempo della crisi. Il Mulino, Bologna, pp. 227–272, 2014.

International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Think Differently: Humanitarian Impacts of the Economic Crisis in Europe, 2013.

International Organization for Migration. Fatal Journeys: Tracking Lives Lost During Migration, 2014. http://publications.iom.int/bookstore/free/FatalJourneys_CountingtheUncounted.pdf.

International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. (2013). Think differently. Humanitarian impacts of the economic crisis in Europe.

International Organization for Migration (2014). Fatal Journeys. Tracking lives lost during migration. http://publications.iom.int/bookstore/free/FatalJourneys_CountingtheUncounted.pdf

McKee, M., M. Karanikolos, P. Belcher, and D. Stuckler. “Austerity: A Failed Experiment on the People of Europe. Clinical Medicine 12(4) (2012): 346–350.

Oxfam. A Cautionary Tale: The True Cost of Austerity and Inequality in Europe, 2013.

Podemos. El programa del cambio. Elecciones autonómicas 2015, 2015.

Sacchetto, D. and F. A. Vianello. Navigando a vista: Migranti nella crisi economica tra lavoro e disoccupazione. Franco Angeli, 2013.

Ukip. Believe in Britain! Ukip 2015 Manifesto, 2015.

Valls, A., Al Coll, and E. Rivera. “Migración neohispánica? El impacto de la crisis económica en la emigración española. Neohispanic Migration? The Impact of the Economic Recession on Spanish Emigration.” EMPIRIA. Revista de Metodología de Ciencias Sociales 29 (2014): 39–66.

Varoufakis, Y. and S. Holland. A Modest Proposal for Resolving the Eurozone Crisis, 2013. http://yanisvaroufakis.eu/euro-crisis/modest-proposal/

References

| 1. | ↑ | http://www.bbc.com/news/business-13856580; Varoufakis and Holland, “A Modest Proposal.” |

| 2, 6, 7, 9, 10, 15, 35. | ↑ | Caritas Europa, The European Crisis |

| 3. | ↑ | Caritas Europa, The European Crisis; IFRC, Think Differently; Oxfam, A Cautionary Tale |

| 4. | ↑ | Greece and Italy have been more strongly hit than Spain by the current arrival of refugees. |

| 5. | ↑ | Oxfam, A Cautionary Tale. |

| 8, 13, 14. | ↑ | IFRC, Think Differently |

| 11. | ↑ | Caritas Europa, The European Crisis, IFRC, Think Differently |

| 12. | ↑ | Forty-three percent of the families assisted by the Red Cross in Spain were unable to afford heating in winter months [IFRC, Think Differently]. |

| 16. | ↑ | McKee, Karanikolos, Belcher, and Stuckler, “Austerity: A Failed Experiment.” |

| 17. | ↑ | Percentage of population over eighteen. |

| 18. | ↑ | http://tracks.unhcr.org/2015/07/the-sea-route-to-europe/ |

| 19. | ↑ | https://www.iom.int/news/irregular-migrant-refugee-arrivals-europe-top-one-million-2015-iom |

| 20. | ↑ | https://www.iom.int/news/mediterranean-migrant-arrivals-2016-near-130000-deaths-reach-418 |

| 21. | ↑ | http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/04/20/world/europe/surge-in-refugees-crossing-the-mediterranean-sea-maps.html?_r=0 |

| 22. | ↑ | http://missingmigrants.iom.int/ |

| 23, 24. | ↑ | http://missingmigrants.iom.int/mediterranean |

| 25. | ↑ | http://frontex.europa.eu/trends-and-routes/migratory-routes-map/ |

| 26. | ↑ | Akalin, “Dispossessed Immigrants”; Carastathis, “Blood, Strawberries.” |

| 27. | ↑ | http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/oct/31/italy-sea-mission-thousands-risk |

| 28. | ↑ | http://www.ecre.org/topics/areas-of-work/protection-in-europe/10-dublin-regulation.html |

| 29. | ↑ | “La paura dell’invasione: ‘La Sicilia non può assorbire una maxi-ondata di sbarchi.’” La Repubblica, February 24, 2011 |

| 30. | ↑ | http://effimera.org/se-questa-e-europa-confini-austerity-e-guerra-di-gabriele-proglio/ |

| 31. | ↑ | http://www.reuters.com/article/us-europe-migrants-orban-idUSKBN0TL0RF20151202 |

| 32. | ↑ | http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/dec/22/anti-islam-march-germany-sing-christmas-carols |

| 33. | ↑ | International Organization for Migration, Fatal Journeys |

| 34. | ↑ | De Luca, “La fatica della resilienza,” p. 235 |

| 36. | ↑ | Bonifazi and Martini, “Il lavoro degli.” |

| 37. | ↑ | Valls, Coll, and Rivera, “Migración neohispánica?” |

| 38. | ↑ | IFRC, Think Differently; Caritas Europa, The European Crisis |

| 39. | ↑ | De Luca, La fatica della resilienza,” p. 232 |

| 40, 41. | ↑ | Collett, Immigration Integration |

| 42. | ↑ | Ukip, Believe in Britain |

| 43, 44. | ↑ | Podemos, El programa del cambio |

| 45. | ↑ | Chen, “What Does Syriza’s Victory Mean” |

| 46. | ↑ | http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2015/07/syriza-survive-austerity-150716073159609.html |

| 47. | ↑ | Caritas Europa, The European Crisis; Oxfam, A Cautionary Tale |

| 48. | ↑ | In the context of the United Kingdom and the destination of many EU migrants, right-wing parties define the circle of belonging even more narrowly by also portraying migrants from southern and eastern Europe as a source of labor competition and a drain on welfare. |