In the midst of two years of highly publicized, often lethal encounters between police officers and people of color in Ferguson, Baltimore, Cleveland, Chicago, New York, and elsewhere, as well as the increasing involvement of police in immigration enforcement mechanisms, a great many people have expressed serious concern about high levels of police activity and abuse in various communities.

O&B asked prominent advocates from the Black Lives Matter, Native Lives Matter, LGBTQ, immigrant, and Muslim, Arab, and South Asian communities about the state of organizing on policing and police accountability in those communities. This is what they had to say.

Contributors

M Adams is a community organizer, movement scientist, and coexecutive director of Freedom Inc. Adams’s dad has been incarcerated most of her life, and she comes from a community extremely targeted by police violence; she is also a dad, and her family is a primary motivation for her work. As a queer black person, Adams uses a strong intersectional approach in venues like the United Nations International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. She is coauthor of Forward from Ferguson, a work in progress on Black Community Control over the Police, and intersectionality theory explain in the paper “Why Killing Unarmed Black Folks Is a Queer Issue.”

Fahd Ahmed is executive director of Desis Rising Up and Moving (DRUM). DRUM organizes working-class and low-income South Asian immigrant workers and youth for worker, racial, educational, and global justice. He has been involved with DRUM for sixteen years as a result of having his own family affected by lack of documentation, deportations, working-class status, and police profiling.

Julio Calderon arrived in the United States from Honduras in 2005 as an unaccompanied minor escaping poverty. Julio started his work with Students Working for Equal Rights by pushing for the DREAM Act in 2010. He later served as the Education Not Deportation coordinator for the state of Florida, which helped to build a campaign around Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. Julio is now the Access to Higher Education organizer for the Florida Immigrant Coalition.

Simon Moya-Smith is a citizen of the Oglala Lakota Nation, and the culture editor at Indian Country Today, an online Native American newsmagazine. His work appears on CNN, MTV, and USA Today. He has a master of arts degree from Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. Follow him @SimonMoyaSmith.

Andrea Ritchie is a black lesbian police misconduct attorney and organizer, whose work focuses on policing of women and LGBT people of color. She is a Senior Soros Justice Fellow and coauthor of Say Her Name: Resisting Police Brutality Against Black Women; A Roadmap for Change: Federal Policy Recommendations for Addressing the Criminalization of LGBT People; and Queer (In)Justice: The Criminalization of LGBT People in the United States. Her new book Invisible No More: Racial Profiling and Police Violence Against Women of Color will be published in 2017 by Beacon Press.

Interview

Q. In 2015, we saw a lot of new energy and attention devoted to increasing police accountability and thinking about how to improve police-community relations across the United States. What community or communities do you represent, and what are its key concerns in the policing space?

M Adams: I am black, working class, queer, gender-nonconforming, and female assigned. These are all identities I am quite proud of and identities that reflect those most impacted by state and structural violence.

Racism, as commonly defined, has two parts: racial prejudice—what I think of as white supremacy ideology—and power. Many tend to focus on the racial prejudice aspect, which often is followed by answers that focus on increased surveillance—body cameras, for example—or increased cultural competency education, implicit-bias training, or counseling for officers. With this focus on reforms that assume individuals are racist, rather than systems themselves, even the best solutions offered can only reproduce the structures that are killing our communities.

We’ve rarely seen reform efforts that address power by actually deconstructing or taking away power from police departments. To be clear, that kind of power and its structures has a name: colonialism. We think the state’s relationship with black communities is a colonial one.

Fahd Ahmed: Desis Rising Up and Moving works with working-class and low-income South Asian-descended communities. That includes people from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and members of the South Asian diaspora, especially in the Caribbean.

We have three main concerns related to policing. The first is surveillance of Muslims and those thought to be Muslim. We have police informants and undercover officers in our communities. We have members of the community being followed, harassed, and pressured into becoming informants. We have cases where informants and undercover police essentially incite and entrap community members, and suddenly you have a so-called terrorism case. Second, we’re concerned about our youth, in particular, being harassed on the street by police use of “stop-and-frisk.” We have cases of young people being stopped ten to twenty times, as many as eighty times by the time they are twenty-one years old.

The third issue is the policing of low-wage workers, especially cabdrivers and street vendors. Some cabdrivers report being stopped and ticketed four to six times a month. The ticketing is so frivolous that if they go to court, the judge will probably laugh it off. So they face a decision about whether to lose a workday or pay out of their pockets for frivolous tickets.

Julio Calderon: I’m undocumented, and I can clearly relate to the struggle of what it means to live in the United States with no identity. I’m one of eleven million undocumented immigrants. I would say 2015 saw a lot of opportunities to build and also create police accountability, but Trump’s comments toward immigrants just helped to criminalize our communities. The deportations continue, and people were already living in fear. When Trump jumped on board with the Republican Party, it allowed racist, anti-immigrant comments, ideas, and even policies to become normalized. Our concerns have grown because we have seen a large increase in proposed legislation to criminalize our communities at the state level. Allowing local police officers to work on immigration enforcement only increases the fear our communities already feel toward the police.

Our concerns have grown because we have seen a large increase in proposed legislation to criminalize our communities at the state level. Allowing local police officers to work on immigration enforcement only increases the fear our communities already feel toward the police.

Simon Moya-Smith: I’m a citizen of the Oglala Lakota Nation, so I represent the twenty-first-century Native American community. While Native Americans are the smallest racial minority in our own ancestral land, we are also statistically more likely than anyone else to be killed by police. We are concerned for the safety and well-being of our indigenous families and the continuity of our cultures, languages, and so on.

Andrea Ritchie: As a black lesbian immigrant, I am part of a number of communities, many of which intersect. Members of these communities experience policing in both similar and different ways. For instance, all experience racial profiling, at times in different contexts and in different forms. As a result, we need protections from profiling based not only on race, religion, and national origin, but also on age, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, immigration status, disability, homelessness, residence in public housing, and tribal status. We also need recognition of gender-specific forms of police violence and effective mechanisms to prevent and ensure accountability for police sexual violence, as well as unlawful searches, including strip searches and cavity searches.

We need to attend to profiling and race-based policing in contexts beyond street and traffic stops, such as policing of “lewd conduct,” prostitution, and poverty; responses to domestic and community violence; child-welfare enforcement; and other sites of gender and sexuality-based police misconduct. Perhaps most challenging, we need to ensure that responses to violence and mental-health crises don’t place survivors of violence at risk of further violence or trauma at the hands of police, requiring us to radically reenvision our approaches to safety.

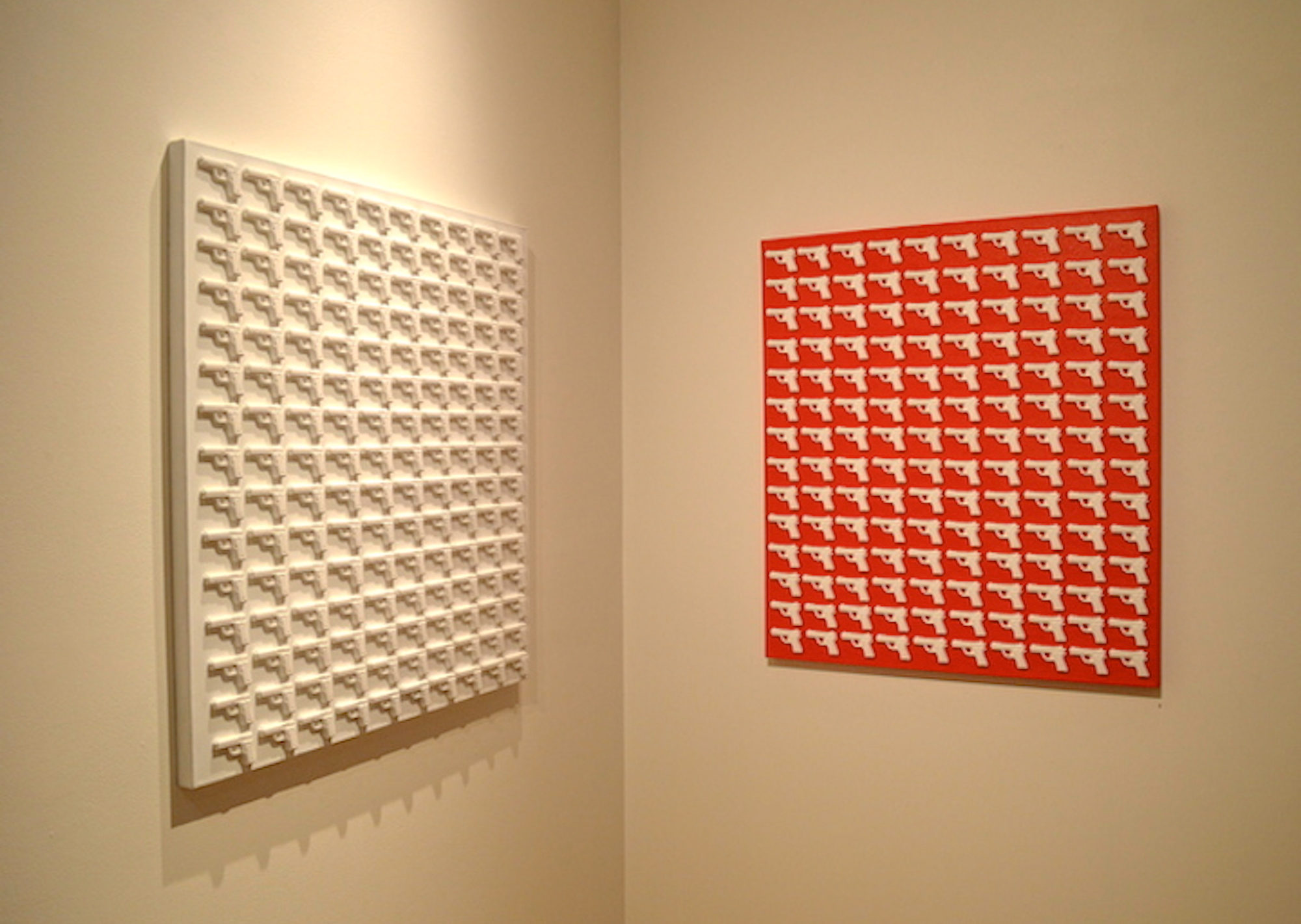

Nafis White | It Doesn’t Show Signs of Stopping

Q. Some people say the police are mostly the high-visibility scapegoats for public-sector problems beyond their control—“bad” schools, a court system rigged against people of color, a political system unresponsive to ordinary people, and so on. What’s your response to that claim?

Julio: The claim might be true to some degree, but the police also have the opportunity to stand with the community, and they haven’t done so in a real way. They should stand with the community and reject the push toward militarization, but they don’t. There is power and control that comes from over militarization, and they love it. They aren’t the roots of the problems, but they help to perpetuate it.

Andrea: Police are definitely on the front lines of creating and enforcing systemic relations of power and privilege, but it is not as if they are without agency or power in doing so. Quite the contrary—police leadership and unions are among the most powerful forces in local and national politics. They drive and are deemed to be the ultimate authorities in debates around crime and safety, and independently, they advance and implement agendas from the “war on drugs” to “broken windows” policing to “zero tolerance” in schools, targeting both individuals and communities of color for enforcement efforts in these contexts. They are far from hapless scapegoats subject to forces beyond their control.

We have defaulted to policing as a response to larger social problems such as poverty, a public-education system that does not serve the vast majority of low-income students of color, and structural inequality, both within and beyond the criminal legal system. We need to divest from policing and punitive responses and redirect resources toward directly grappling with and addressing these issues in ways that actually increase safety for everyone.

Simon: There are public-sector problems; that is incontrovertible. But there is also systemic racism in police culture. For example, a Navajo woman was recently shot and killed by police because she allegedly had a pair of scissors in her hand. Meanwhile, somewhere, a white man brandishes and waves a gun, yet he lives to see another day. That is a demonstration of the systemic racism found directly in police departments.

M Adams: It is true that black communities are exploited and oppressed in every single sector. As a result, black people experience the concentrated effect of violence on our lives. It is not only in interactions with the police that our lives are precarious.

However, the failure of these sectors in addressing black people’s needs does not excuse the police for the violence they also perpetuate against us. The police are not guiltless, objective arbitrators, as conventional narratives often situate them to be—making them the omniscient “good guys” and us, not so. And, to be frank, even those who are poor, uneducated, and without services or respectability— the ones who are not “good”—is it really too radical, too beyond the pale, to demand that if they encounter the police that they too should live?

even those who are poor, uneducated, and without services or respectability— the ones who are not “good”—is it really too radical, too beyond the pale, to demand that if they encounter the police that they too should live?

This is why we demand community control over the police—to ensure their right, our right, to life. This moment gives us an opening to assert our humanity, freedom, and human rights in policing—but this analysis applies to all sectors. We need to take power from structures and institutions and place it in the hands of the people who are most vulnerable and impacted.

Fahd: The police are responsible for the parts they’re responsible for, including the ways they relate to these other institutions. For example, in New York police resist efforts to redirect monies spent enforcing current school-disciplinary practices to restorative-justice approaches. Police advocate for growth in their own budgets even when that undercuts support for social services to meet basic community needs. Yes, the education system, the court system, and the political system are all part of the bigger problem, but so are the police, including unions and police departments.

We’re in an era when policing is thought to be the solution to every social problem. Issues in schools? Minor crime in neighborhoods? Bring in more police! We think one of the primary ways to invest in what we really need—job creation, community building, rebuilding our education system—is to begin divesting from police.

Q. A number of different US communities—African Americans, immigrants, LGBTQI, Muslims, Arabs, and South Asian Americans, among others—have serious concerns about police behavior. To what degree are your community’s interests and strategies aligned with those of these other communities?

Simon: Native Americans are the first nations of this land, our ancestral land. We were the first to be enslaved and sold by white men. We were the first to be murdered and mutilated for the color of our skin. Our interest has always been to save our children, to protect our families. Our strategies have always been to rehumanize ourselves in the eyes of those who dehumanize us. Still today we are dehumanized, most visibly in the form of sports mascots. The term “redskin” refers to a way of proving the death of an Indian—by showing our scalps. In a nation where a genocide against us occurred, where an estimated one hundred million indigenous people died as a direct consequence of aggressive Christian imperialism and domination, and where we are still murdered today by police—and they still receive medals for killing Indians—our interest has been for more than five hundred years to survive into the next century.

We were the first to be murdered and mutilated for the color of our skin. Our interest has always been to save our children, to protect our families. Our strategies have always been to rehumanize ourselves in the eyes of those who dehumanize us.

Julio: Our communities are very interested in working with every community mentioned. I have to admit it has been hard: we are always intentional in creating those spaces, but there’s been little continuity and follow-through. There is so much to learn from each community, and the liberation of one is tied to the liberation of the other. For example, we have a clear and shared interest in shutting down private prisons, and I believe we can accomplish that only if we come together.

Andrea: First, it is critical to recognize intersections among those communities—for instance, among LGBTQI communities, and how LGBTQI people of color bear the brunt of discriminatory policing.

Secondly, what happens during stops—harassment, verbal abuse, physical violence—may look the same across communities, or it may take more specific forms. For instance, for black, immigrant, or LBTQ women, it may be sexual abuse of the kind perpetrated by Oklahoma City police officer Daniel Holtzclaw, or strip and cavity searches in the context of the “war on drugs” or policing of gender, or police violence against pregnant women. For immigrants, a stop may become a path to immigration detention or deportation, and to abuse by immigration authorities as well as police.

For lesbians, policing of gender and sexuality informs race-based policing from the names we are called, to assumptions made about our behavior, to the lack of protection from violence by those closest to us and our communities at large. For South Asian, Muslim, and Arab communities, it can turn into a “terrorism” investigation, with devastating consequences.

In light of these common and divergent experiences, there is no question that our interests are aligned and that we need to hold these complexities.

Fahd: I think about it on three levels. First, we’re very intentional about doing political education with our own communities and membership, for example, showing the evolution of policing in the United States from slave patrols and the repression of workers. We want to ensure that people have the basic political education they need to understand the systems with which we’re contending.

Second, we facilitate relationship building between our members and the members of other organizations and directly-impacted communities: through exchanges, guest speakers, or visiting other organizations. That relationship building helps people bridge gaps and understand each other and understand how the same institutions are targeting different groups in both similar and different ways. Third, we engage in collaborative struggle with other communities.

Putting these three together allows people to think about how we can pursue our interests without undermining the interests of others, and how we can shape our struggle in a way that’s inclusive of all communities. So, for example, many of our youth are subject to bullying in schools, often at the hands of black or Latino youth. Where we used to call for zero-tolerance policies, which led to the disproportionate suspension and expulsion of other youth of color, now we call for restorative-justice practices. Now we aim to build community across groups of students so that antagonisms are resolved rather than deflected by use of punitive measures. We use a similar alignment around other issues.

many of our youth are subject to bullying in schools, often at the hands of black or Latino youth. Where we used to call for zero-tolerance policies, which led to the disproportionate suspension and expulsion of other youth of color, now we call for restorative-justice practices.

M Adams: Intersectionality is at the heart of how we do the movement work we do. In part, this is because myself and those I organize alongside are black, Southeast Asian, queer, trans, disabled, poor, immigrant, and wimmin experiencing mental-wellness challenges, across the life-span, and are just plain struggling to keep things together. Our work is to build family, in the stead of solidarity, because it takes this level of commitment to really build across identities toward collective liberation. We keep these intersections at the fore through our analysis and campaigns.

We use an intersectional human-rights framework that is noncompetitive but sharp enough that the uniqueness of each community remains central and crucial to how we do the work. This analysis was at the root of an intersectionality paper and challenge entitled “Why Police Killing Unarmed Black People is a Queer Issue.” The challenge to mainstream LGBT organizations is to center blackness and the current struggles against police as primary, rather than focus on marriage and shortsighted-policing reforms. It is necessary to hold each other up across identities in recognition of the fact that we are all surviving in and against the same racist colonial structure.

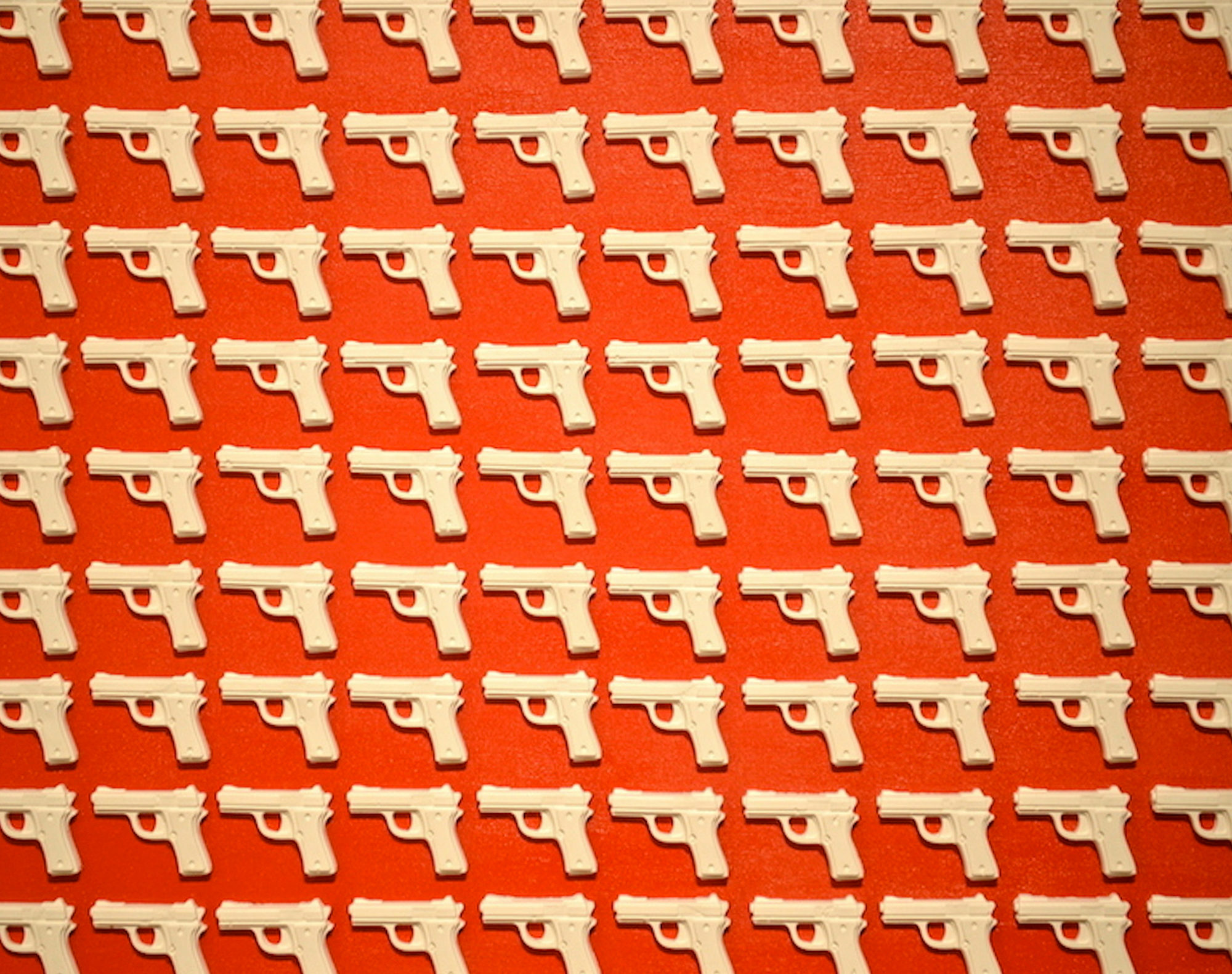

Nafis White | It Doesn’t Show Signs of Stopping, 2013 (detail)

Q. What key lessons from your police-related work in 2015, and possibly earlier, did you bring into 2016?

Andrea: In 2015, we saw unprecedented attention to women and LGBTQ people’s experiences of policing, from the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing to the Twittersphere to the streets. It brought this incredible energy, along with over twenty-five years of research, documentation, organizing, advocacy, and litigation around the experiences of black women and LGBTQ people and women and LGBTQ people of color, into 2016, with the hopes of seizing on this momentum to move the conversation even further so that we begin to see real change. One key lesson is to think beyond visibility of women and LGBTQ people of color’s experiences of policing within the larger context of racial profiling and police violence, and to begin to ask ourselves how these experiences require us to expand and shift our strategies and advocacy agendas.

M Adams: Two things. First, we must build power within black communities. By this I don’t mean listening, though that is certainly important. I mean black and other deeply affected people must be lifted up as the leaders, the policy analysts, and the theory builders. This is a necessary step to societal transformation.

Second, we need enough ideological clarity to be able to discern between reform-based solutions, which are clever ways in which colonialism and neocolonialism reinvents itself, versus smaller shifts of power, which lends itself toward a trajectory of transformation. As a revolutionary I believe all power belongs to the people. I know this will not happen overnight. Therefore, we need a metric and orientation toward the proposed solutions in the interim. Does the proposed reform reduce or end suffering (e.g., monies divested from policing into education, shorter jail sentences)? Is there a true shift of power from the state to the people (e.g., civilian boards with subpoena power, community control over the police)? A sharp analysis gives us insight into things that mislead us, like body cameras.

To me, it’s clear that we must organize around suggestions that shift power.

Fahd: One of our most important lessons was about how to build cross-community solidarity at the grassroots level, among people who suffer the brunt of police abuses, along the lines I talked about before with respect to restorative justice rather than zero-tolerance policies. We also saw that we hadn’t always been thoughtful and consistent about what we mean by police reform. So the use of body cameras might seem like a good idea, but ultimately their use simply increases the flow of funds to police departments.

You can’t solve the problem of police abuse by throwing more money, resources, technology, and equipment at police departments. We have to reduce the footprint of policing in our communities and across the country and invest those resources in our communities and institutions in ways that reduce the need for police in the first place.

You can’t solve the problem of police abuse by throwing more money, resources, technology, and equipment at police departments. We have to reduce the footprint of policing in our communities and across the country and invest those resources in our communities and institutions in ways that reduce the need for police in the first place.

Julio: I believe the police find it hard to see the humanity of a person of color; they see no value in us. In the eyes of many of them, we are disposable. But there are opportunities for them to take a stand and join us. A few of those moments have happened and need to be repeated. The system has been created to keep our movement and the police separated and antagonistic to each other, but I remember seeing a video where the police took off their helmets and joined the protesters. We need some of that this year.

Simon: The key lesson is that Native Americans are still here and that we are most likely to be killed by police.

Q. What are your main goals with respect to policing over the next two to three years, and how are you working to achieve them?

Fahd: We want to build the capacity of communities targeted by police to lead the fight themselves by building the base, building their capacities, and providing opportunities to learn how to fight back. And we want to engage in campaigns for police reform. The principles in those campaigns will include not harming other communities, building solidarity across communities, and not giving greater power to police in any way. We don’t have the people or strength to completely overhaul policing. But we can teach people how to fight and increase the base of people interested in having the fight.

Simon: My main goal is to remind people that racism is at the bedrock of this nation. That if you are not Native American, you are the direct beneficiary of aggressive Indian removal policies and actions. People say that their family has “always fought for this land.” Bullshit. There are restaurants in Europe older than this country. I want to remind people that twenty troops of the US Seventh Cavalry received the Medal of Honor for their participation in the Wounded Knee Massacre in December 1890.

That racism has been at the foundation of authority in this country before there were any other races here except for we, indigenous peoples, and the white man. Our goals are to achieve unmitigated recognition of what this country has done in order to fully comprehend what it is doing and why it’s doing it. Know your history, Jack.

M Adams: The first thing we seek to accomplish is to build out a clear analysis of the fundamental problems that face us. If we don’t have a clear sense of the fundamental problems, it is impossible to truly dismantle the structures that cause them. For us, this means developing our analysis about the conditions that black people in the United States face—to understand that what we need to focus primarily on are structures and systems, not racist attitudes and dispositions. It is a charge to address the colonial relationship that black communities are subjected to in the United States, and not to focus on improving attitudes or relations of state actors. We must build ideological clarity on the issue and how to address it.

We also seek to build a base of those most impacted and to build movement infrastructure that is sustainable through the different crises our communities experience. We want long-term organization. This means people most impacted develop a shared analysis, build unity around a common vision, develop their skills to address the problems faced, and resist!

Andrea: My goals are to ensure women and LGBTQ people of color’s experiences drive our analysis of racial profiling, police violence, and violence against women and LGBTQ people, as well as agendas for change. I’m pursuing that in multiple ways. One is working toward implementation of recommendations of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing of particular importance to women and LGBTQ people, through federal advocacy and supporting local advocates to ensure implementation on the ground. I am also continuing to think through what bringing women and LGBTQ people’s experiences to the center means for solutions being advanced—whether it’s body cameras, special prosecutors, or civilian oversight and control of policing.

My goals are to ensure women and LGBTQ people of color’s experiences drive our analysis of racial profiling, police violence, and violence against women and LGBTQ people, as well as agendas for change.

In 2016 I will also continue to push for examination of how police responses to violence produce further violence and punishment rather than protection for all too many women and LGBTQ people of color. These experiences demand that we envision new approaches to safety—whether it’s revisiting mandatory-arrest policies that produce disproportionate arrests of women and LGBTQ people of color, who are survivors of domestic and interpersonal violence, while failing to produce increased safety, or developing alternate responses to mental-health crises that don’t involve police.

Julio: The collaboration between Immigration and Customs Enforcement and police increases deportations and fear in our communities. We need to increase and protect the sanctuary cities. That is a very clear goal and helps us have an idea how to work and build at a local level. If the number of sanctuary cities goes up, the number of deportations will decrease drastically.

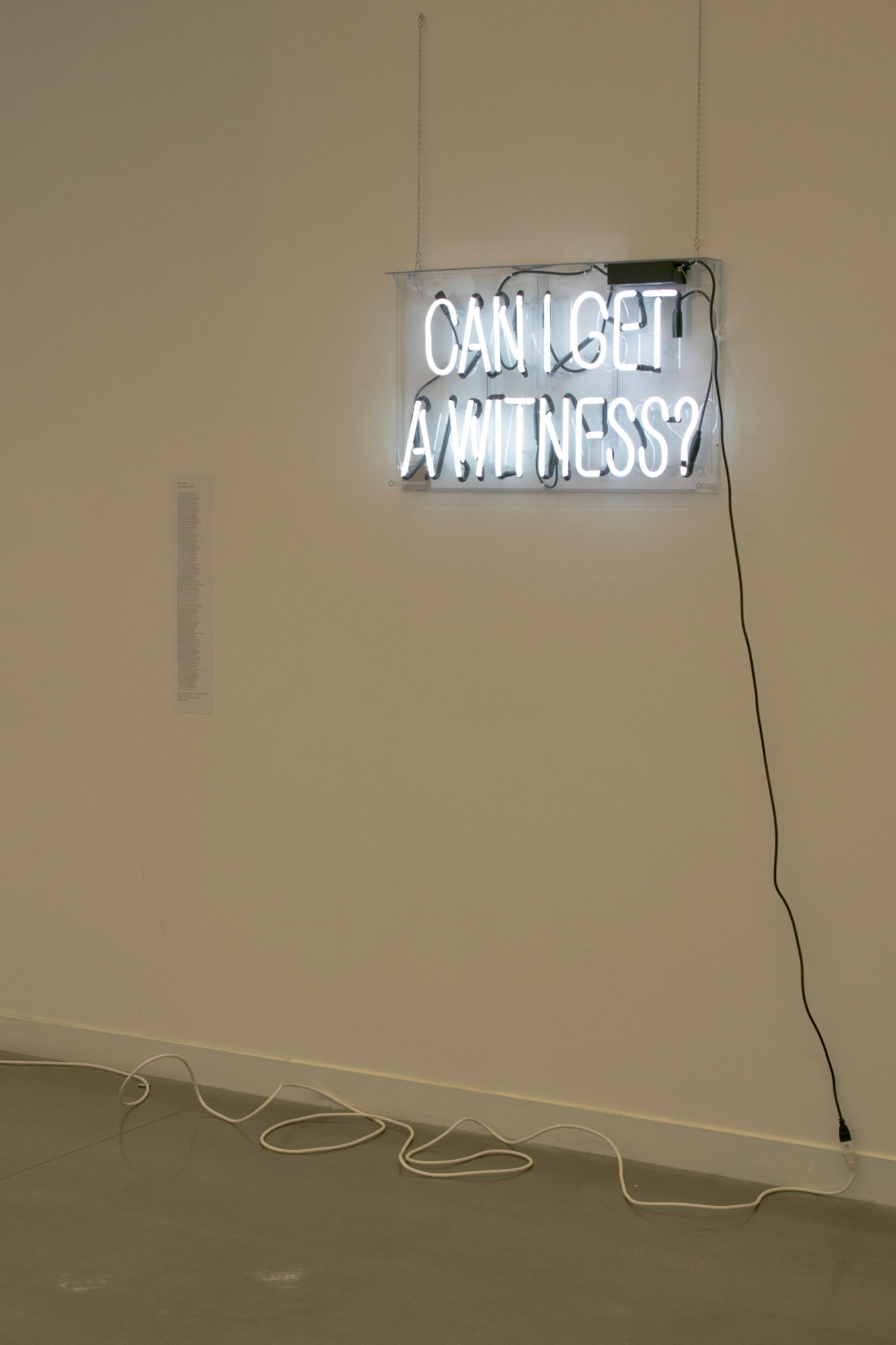

Nafis White | Can I Get A Witness, 2014

Q. Many years from now, as you bounce your grandchild on your knee, give us one image that captures the new era of policing—with respect to your community—that your work will have helped bring about.

M Adams: There will be complete community control of the police. What I mean by this is that communities will have all the power to decide and develop their vision of what a secure and safe community is and how security and safety are maintained. In the interim that means we fight for the ability to hire/fire officers, have officers who live in the communities they serve, and have communities determines the priorities, policies, and practices of police institutions. Essentially, this means creating a democratic structure of policing.

In order for this to be real, we know ultimately that the police and policing institutions of today must be abolished. In their stead, communities will determine how to make their own communities safe. We will have brought this transformation about by offering analysis of the current system, as well as theory and method for how to bring about change that puts power in the hands of communities.

Fahd: On the macro level, we would prioritize human needs and human development of all rather than things like efficiency and profits. We’d see a shift to giving primacy to the development of whole human beings and of their social, economic, psychological, physical, and spiritual well-being, both individually and collectively.

Secondly, there are structures in place to allow communities input, decision-making, and control over the institutions that affect their lives, including systems of policing, education, and economics—these and the other basic structures and institutions that exist in our society. To do all this we’d have to do away with all the implicit and explicit hierarchies we create among ourselves based on race, gender, sexuality, geography, and more. We’d need a truly egalitarian understanding of human beings.

Julio: My image is of unarmed police working to help the community. We need to stop allowing police to enforce the laws a few create to profit, control, and kill. I envision an officer engaged in every aspect of the local community, which will bring about much greater trust and better communication. I want my grandchild to feel protected and inspired when next to an officer, like he would feel next to a family member.

Simon: “You know, my dear, they never lifted the bounty on Native American heads. So the hunt continued into 2016. The authorities were killing all of us, and the bastards were still getting medals for killing Indians. And we couldn’t get the mainstream media to talk about the killing of our people either. Not black reporters. Not Latino reporters. Not gay reporters. Not Asian reporters. No one, my dear. At least not enough. The conversation was binary on the matter of police brutality: black and white. Black and white. Black and white. And then, when we tried to talk about police killing Native Americans more than any other race, we’d get, ‘We’re not talking about that right now! You’ll have your chance!’ But we never did.

“Back then, Americans would attend Washington R-word football games in red face, and then they’d tell us that they were ‘honoring’ Native Americans—that red face ‘isn’t racist.’ Meanwhile, a cop would kill another Native American and then another and then another, and hardly any news outlets would say anything about it. We were cancelled out of the American conversation on almost every subject. A cop tried to kill me once, but he missed. That’s why I don’t have a knee to bounce you on. Not much has changed since then. We’re still not human to Americans, not in their eyes. We remain ‘the Indian problem.’ The myth. The mascot. That thing to be ridiculed and dehumanized in service to their greed and self-interest.”

we will be talking about what our responsibilities are to each other and to those around us to ensure the safety of all members of our community in ways that don’t involve policing and punishment, but rather care, community accountability, structural equality, and radical personal and societal transformation.

Andrea: Instead of having to give my grandchild a comprehensive “know your rights” training and brainstorm strategies for safety and surviving police encounters, we will be talking about what our responsibilities are to each other and to those around us to ensure the safety of all members of our community in ways that don’t involve policing and punishment, but rather care, community accountability, structural equality, and radical personal and societal transformation. We will be dreaming of a world without police and prisons, actively working to bring it into being together.